I'm Not Sure if I Buy the Idea of Sacraments as a Means of Grace

Some thoughts on Baptism and Communion (1/3)

In the Church of Christ, we typically don’t talk about sacraments. Well, we do, but we don’t. We do in that we emphasize baptism, Lord’s Supper, and, to an extent, confession. But I don’t think I ever heard them described as sacraments. After all, we call Bible things by Bible names, and a quick search reveals the Bible contains no such term.

So, case closed. I’ll see you all in next week’s article.

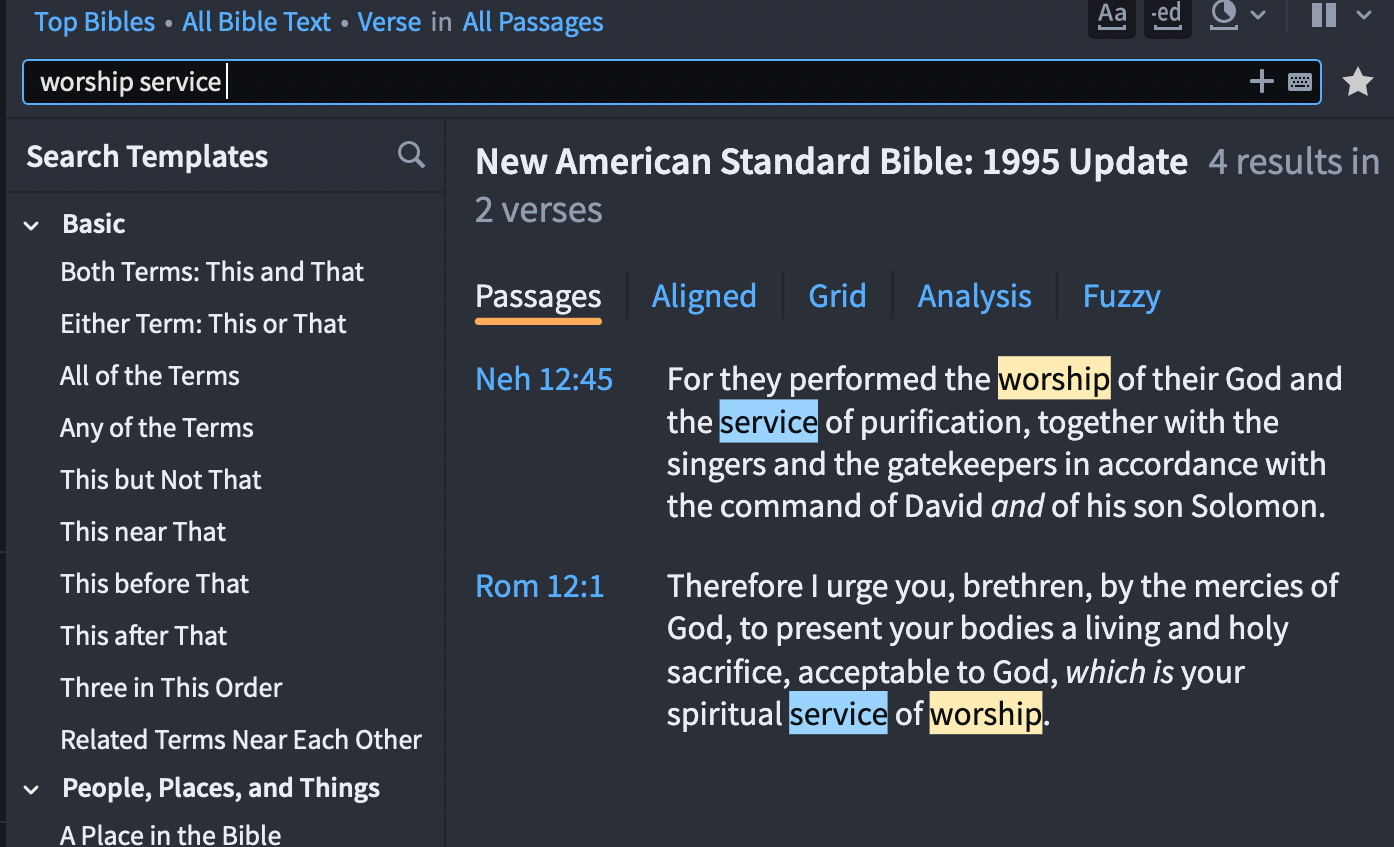

Okay, maybe we’re not done just quite yet. By the way, don’t search “plan of salvation” or “worship service” if you don’t mind. We don’t want to throw the baby out with the bath water.

Ahem… Necessary inferences and all that. Expediency. Prudent. Implied. One must assume a song requires a song leader. Yes, yes.

So, let’s talk sacraments.

What is a Sacrament?

Augustine of Hippo defined sacraments like this:

On the subject of the sacrament, indeed, which he receives, it is first to be well impressed upon his notice that the signs of divine things are, it is true, things visible, but that the invisible things themselves are also honored in them, and that that species, which is then sanctified by the blessing, is therefore not to be regarded merely in the way in which it is regarded in any common use.1

Or to put it another way, sacraments are the “visible form of invisible grace.” Or to put it another way, sacraments are an “outward sign of an inward grace.”

So the sacraments may be everyday objects like water, wine, and bread, but when they are blessed, they become something more and “not to be regarded merely in the way in which it is regarded in any common use.”

That is, baptism is more than a bath, and the communion is more than a meal.

The Sacraments of the Church of Christ

Baptism

In the Church of Christ, we treat baptism seriously, and we don’t want anyone to make light of it. Some churches and camps I’ve been a part of discourage clapping at baptisms because they see it as a time of worship and people don’t typically clap during worship in the COC. I don’t have any problem with that now, by the way, but it used to make me uncomfortable.

Communion

When I was growing up, Mrs. Martha made the best communion bread. After worship, we would go into the back and eat whatever bread was left over and polish off all of the grape juice. I remember on some occasions that there were adults who didn’t particularly appreciate that.

I had a friend telling me just yesterday that her son and his friends got in trouble for eating the rest of the communion elements. When she asked what the lady was planning on doing with it, she said she intended to throw it away. My friend asked how throwing it away was more respectable than letting the teenagers just eat the rest.

The point is that we hold these two rituals in high esteem within the Churches of Christ. While we may not have called them sacraments, that’s what they were.

Confession

In some churches, confession is identified as a sacrament. It’s also called the sacrament of penance or the sacrament of reconciliation. If you’ve watched a lot of movies, you’ve probably seen someone go into a closet where they sat on one side of the wall opposite of a priest and said, “Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned.”

Well, we may not do that in the Church of Christ, but “going forward” and making a public confession is seen as a necessity and a prerequisite to forgiveness (1 John 1:9). The typical rule is that “confession should be as public as the sin.”

When I got into a fight in the seventh grade and was suspended for three days, my grandmother made a motion towards the front pew during the invitation song following the next sermon to nudge me to go forward.

While it’s not usually counted, I think we, to varying degrees, treat confession as a sacrament.

Marriage

Marriage is considered a sacrament in some churches, but it’s not usually considered a sacrament in the Church of Christ. However, in some circles, marriage is usually only encouraged and supported between two Christians (read “members of the Church of Christ”), and I think when that happens that we come close to treating marriage as a sacrament.

This could also be said about our rules concerning divorce and remarriage, but I wouldn’t count this one like I come close to counting confession.

Summary

Basically, I see baptism and communion as sacraments within the Church of Christ. I might include confession, and I may rarely count marriage.

But What Do They Do?

There is a disagreement among Christians as to what the sacraments do. Some would say that the sign bestows or contains grace. Others would argue that it is only depicts, symbolizes, or represents grace.2

In the Church of Christ, we approach baptism and communion differently.

Like many evangelicals and other more “low church” denominations, we view communion as a representative of the body and blood of Jesus. It points to the work of Christ on the cross and does nothing outside of symbolizing the grace we received through Jesus.

However, we differ from these same believers because we see baptism as a sign that bestows or contains grace. That is, there is something more transactional about the way we view baptism. To put it simply, one must receive the sacrament of baptism in order to be saved, and one is not saved without or before baptism.

This is not a position I hold any longer, but I remember when I would talk to my Baptist friends, for example, they would argue that baptism is an outward sign of an inward grace. That is, one is baptized because they are saved.

The Sacraments and Pattern Theology

Communion

Let’s start with communion because I think that’s the easiest to deal with first since most of my readers come from a Church of Christ background.

I don’t see communion as a means of receiving grace. While I think we toe the line when we say that one must take communion every Sunday, we still would argue that it is symbolic. This insistence upon weekly observance of the Lord’s Supper is more about following the so-called pattern of worship and not receiving some kind of blessing through receiving the sign (outside of the benefits of meditating on the love of God, etc.).

The Elements

But let’s talk about the particular elements of communion, also called the emblems. Most Churches of Christ that I’m familiar with use some form of unleavened bread and grape juice. Unleavened bread may differ from congregation to congregation. Some churches use oyster crackers while others use Matzos bread from Walmart. Others make their own bread, which is usually pretty tasty.

I’ve never heard anyone condemn someone else over the kind of bread they use as long as its unleavened, but I think we can all stand together in condemning the styrofoam discs we were forced to take during COVID, right? Those things were awful.

So outside of debates about salt in the bread or whatever, I think our style of bread is typically the same.

Grape juice, or the fruit of the vine, on the other hand, is a little more controversial. The big question in whether or not it can be fermented (wine) or unfermented (Welch’s). In my experience, most churches use unfermented grape juice in communion unless Sister Suzy leaves it out on the counter over the week.

And I think this last paragraph is the most telling in what I’ll be trying to get at. Why do we use grape juice at all? Well, because we have to use “fruit of the vine” (Matthew 26:29). But why do we have to use it just because Jesus mentioned it in that passage? Well, that’s what they used then, and since Jesus instituted the pattern, we must follow the pattern.

But why don’t we use wine? Well, because we believe that one drink drank is one drink drunk, and since drunkenness is a sin, Jesus was obviously talking about grape juice (Jesus made sparkling grape juice in John 2 of course).

So all of this is because we are following a pattern of worship that we think is prescribed in the New Testament, but we modify it because of our cultural assumptions about the permissibility of alcohol?

Well if that’s why we use fruit of the vine in communion, why did they?

They used it because it is what was available. Wine was standard in the Passover meal and part of daily life. Craig Keener observes that by the time of the first century, there were four glasses of wine consumed during Passover to commemorate different aspects of the Exodus and Israel’s future.

Four cups of red wine came to be used in the annual Passover celebrations, and if these were in use by the first century (as is likely), this cup may be the third or fourth. The leader of the group would take the goblet in both hands, then hold it in his right, a handbreadth above the table.3

Here’s a question for you: was Jesus intending to initiate a ceremony or ritual, to be observed weekly, in which a little sip of grape juice and small bite of bread would be consumed? Or was he taking something common in every meal and saying that whenever they ate together that they should take a moment to remember why they are all there?

Personally, I find the latter more compelling, and I do not see any basis for our weekly ritual in Scripture at all. I think that what we do is so far outside of the imagination of the first century saints that to demand that others follow this pattern precisely or to argue about particular arrangements of it, is to totally miss what communion meant to the first century saints.

But that doesn’t mean that I think the way we do it is wrong. I have no problem with it. I’m just saying we are kidding ourselves if we think what we do on Sunday does any so-called “pattern” justice.

Eat My Flesh and Drink My Blood

Where is the Lord’s Supper in John? In the last supper account, John 13-16, there is no mention of Jesus taking bread and taking wine and telling his disciples to do this in his memory like there is in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the synoptic gospel accounts.

But we do have an odd interaction between Jesus and his audience recorded in John 6.

Before we get there, we need to make a few observations. First, Jesus did not institute the Lord’s Supper until the night that he was betrayed (1 Corinthians 11:23). Which means that when Jesus said what he did in John 6 about his flesh and his blood, there is no reason that the disciples then would understand that to mean the bread and wine we receive in the Lord’s Supper.

Of course, the gospel accounts are not like movies where we are watching the events unfold in real time. Instead, they are passion narratives told with a particular agenda in mind. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, though they tell the same story, often vary in the details. Only Matthew and Luke contain a birth narrative. John includes the cleansing of the temple shortly after Jesus’s baptism. Matthew and Luke switch the order of the temptations. And that’s just to name a few.

So to say that the characters in the narrative in John 6 did not know about the Lord’s Supper and the explanation of Jesus in the synoptics is not to say that John and his audience didn’t know about it.

But what we can ask is what Jesus meant by these sayings within the context of John 6.

In John 6, Jesus feeds five thousand with the help of a young boy who provides five loaves of bread and two fish. After feeding them, he flees into the wilderness because he perceives that they want to make him king. Eventually, the people catch up with Jesus and ask him why he left. His response is basically that they only want him for the bread he miraculously gave him and not for what the miracle signified.

After a lengthy discussion about bread, the exodus, miracles, and eternal life, Jesus says that God can give them bread that will produce eternal life within them. When they ask for this bread, Jesus says, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty” (John 6:35).

At first, the people get offended because Jesus claimed to come down from heaven, so Jesus doubles down on his challenge:

Very truly, I tell you, whoever believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life. Your ancestors ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the bread that comes down from heaven, so that one may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever, and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh. John 6:47–51

After Jesus said this, the people expressed some confusion, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” Jesus’s response added to the confusion when he became even more explicit:

So Jesus said to them, “Very truly, I tell you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you. Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day, for my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me and I in them. Just as the living Father sent me and I live because of the Father, so whoever eats me will live because of me. This is the bread that came down from heaven, not like that which the ancestors ate, and they died. But the one who eats this bread will live forever.” John 6:53–58

After this odd exchange, his disciples approach Jesus and want to know exactly what all of this means. Surely Jesus doesn’t want them to eat his actual body, right? After all, cannibalism is generally frowned upon.

So, Jesus finally speaks plainly, “It is the spirit that gives life; the flesh is useless. The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life. But among you there are some who do not believe” (John 6:63–64).

This entire time he wasn’t talking about actual flesh and actual blood, and he didn’t clue them in on communion. Instead, he wanted them to follow his words and believe in the One who sent him. This passage may seem like a communion text to us since we are living on the other side of the death of Jesus, but if we read this in its context, its simply talking about having faith in Jesus and following his teachings.

While the bread and juice we receive on Sunday morning may symbolize this, that is all it does. Faith in Christ and transformative obedience to his teachings is how we have eternal life. It is how we eat the flesh and drink the blood of Jesus. It is how we taste of this bread that came down from heaven.

Week By Week?

In the Church of Christ, we take communion week by week because, we are told, it follows the pattern of the New Testament church, and in order to be the New Testament church we have to do what they did. Everyone else, we are told, are members of a fraudulent body masquerading as the church of Christ.

But where does this idea come from? If what I’ve said in the recent sections about communion is true, then how did we get the idea that the specific elements of the juice and the bread need to be taken weekly… or else?

In the second century, communion began moving away from a full meal enjoyed by believers. Here is an excerpt from an article on communion in the Lexham Bible Dictionary:

By the third century, the link between the Lord’s Supper and the communal meal was declining and had disappeared altogether in some places. Eucharistic services were found in cemeteries and separated from worship in other unique rites. The bishop or priest came to be seen as the sole agent involved in the rite, rather than the people as a whole. By the fourth century, as Christianity became more mainstream, it became common for members to attend church without participating in the Eucharist at all, since the sacrament required rigorous scrutiny of one’s life; this encouraged the view that the Lord’s Supper was an activity for the clergy and not common members (Bradshaw, Origins, 114–15, 142–43). At this point, the Eucharist was well on its way toward becoming a sacerdotal rite fully removed from the common life of the Christian community.4

The Didache, a collection of late first century or early second century teachings, dictates the prayers to be said before and after eating the bread and drinking the wine. The prayers after the Lord’s Supper are to be said when one was “satisfied” because God “didst give food and drink unto men for enjoyment” (Didache 10.1, 3). The true significance of this meal though is what I’ve been trying to explain in this article: “but didst bestow upon us spiritual food and drink and eternal life through Thy Son.”5

So, how often was this meal received? Weekly? Eventually it was, but to begin with, the saints broke bread daily (Acts 2:42-47). Was this departure from a daily meal a departure from some New Testament pattern? Not in any official sense.

But it does demonstrate the malleability of the meal.

Our way of taking communion isn’t based off of any first century practice; it is an adaption of a more ritualistic practice that emerged after the first century.

Which brings me to the point: there is nothing wrong with the way we take communion now, but there is something wrong with taking our preferred way and demanding it over any other preferred way.

Believe me, I prefer taking communion weekly, but I also think we should take a moment to remember Jesus before every meal, especially, but not limited to, those involving bread and wine.

Baptism

This article is already way longer than I expected. I’ll cover the baptism portion next week :)

Augustine of Hippo. “On the Catechising of the Uninstructed.” St. Augustin: On the Holy Trinity, Doctrinal Treatises, Moral Treatises. Ed. Philip Schaff. Trans. S. D. F. Salmond. Vol. 3. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1887. 312. Print. A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, First Series. 26.50

Schlesinger, Eugene R. “Sacraments.” In The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, Rachel Klippenstein, Douglas Mangum, Carrie Sinclair Wolcott, Lazarus Wentz, Elliot Ritzema, and Wendy Widder. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

Keener, Craig S. The IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993. Print.

Gamel, Brian. “Lord’s Supper.” Ed. John D. Barry et al. The Lexham Bible Dictionary 2016: n. pag. Print.

Lightfoot, Joseph Barber, and J. R. Harmer. The Apostolic Fathers. London: Macmillan and Co., 1891. Print.