A Guy With a Beard and a Boat

Some thoughts on Noah

Here’s a fun kid song.

The leader sings it and the kids repeat. Be sure to exaggerate the parts in italics.

Here is Noah. (hold up a finger)

Here is the boat. (cup your hands)

Down came the rain. (spirit fingers all the way down)

And the boat it float. (make the boat float)

And the people criiiiieeeeddd. (look distraught)

And the people drowned. (hold your nose on the last word)

Out walked Noah! (sing this part cheerfully. Imagine a guy swinging his arms while walking down the sidewalk in at typical movie from the 50s-60s that features the perfect American neighborhood)

On the dry ground. (“he’s safe” motion like in baseball)

Yep, so maybe not that fun. Most kid songs talk about children in the muddy muddy and how the animals came by twosies. This one points out the fact that’s left off of the nursery walls: people drowned.

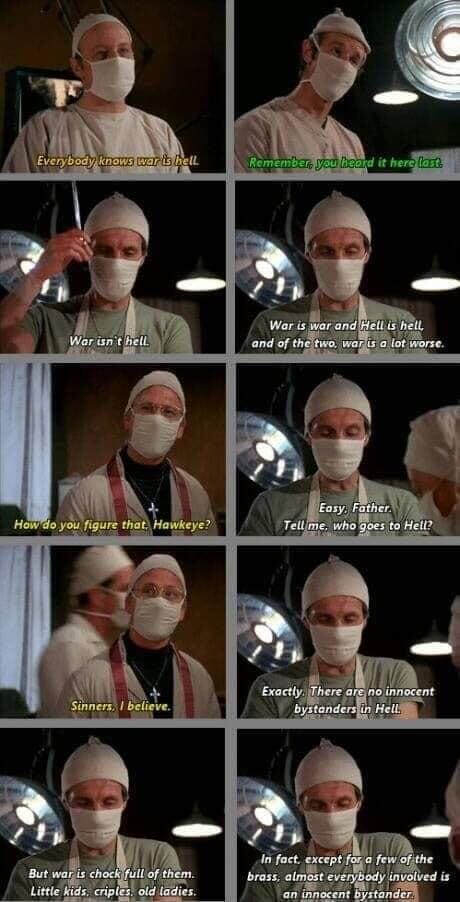

In our post-Oppenheimer world, the idea of killing an entire city of people with no discrimination is a bit unsettling to say the least. As Hawkeye observed in the show MASH, “There are no innocent bystanders in Hell, but war is chock full of them – little kids, cripples, old ladies. In fact, except for a few of the brass, almost everybody involved is an innocent bystander.”

So when I read the flood story, I can’t help but cringe a little bit… or maybe a lot.

When we read the stories of the Exodus or the Christmas narrative, we think how awful it is that Pharaoh or Herod would kill all of the young Hebrew males. In light of the abortion debate, some have used these stories to make a fairly straightforward point…

But there’s a problem.

What about the flood?

If all life is sacred, and if murder is intentionally taking the life of an innocent human being, and if babies are sinless (my tradition rejections original sin), then was the flood not God intentionally taking the lives of every human on earth including the innocent human babies?

What do we do with this?

So, imagine my surprise when I was asked to talk about how God is “Surprisingly Faithful” in the Noah story to a bunch of teens visiting our congregation for a youth devotional.

This blog post is how I approached the subject. I hope what I came across in my research will help resolve this tension for you as it did for me.

First, Can We Just Be Honest

Can we be honest that the picture of God we get through Jesus, who is the perfect representation of who God is (Hebrews 1:3), doesn’t really match with the God we read about in Genesis 6, at least in the way we are expected to read it? And I totally understand that this may just be my humanity.

But can we just be honest that the God who causes the sun to shine on the just and the unjust, is kind to ungrateful and evil men, loves the whole world, is love, and desires all to be saved doesn’t seem to be the kind of Being that would kill every single person on earth, including children, with a flood?

I’m not saying that it didn’t happen like that. All I’m saying is that I can’t be the only one who thinks there has to be more to the story, right?

Even when I was a kid singing that song that I quoted earlier, I felt like it was a bit brutal. Another song we sang, Jesus Loves the Little Children, talks about how Jesus loves all of the children of the world. What about those children who must have been scared as the flood waters surrounded them, separated them from their parents, and filled their lungs with water?

Would Jesus’s Father send violent waters to sweep an infant out of her mother’s arms and into the depths below?

I’m just trying to be honest by saying I have a tough time accepting this.

After all, I was told to love my enemies. And when Jesus wept over Jerusalem during the last days of his life, I think that means that God must have wept too.

So how on earth do we read this story and keep our sanity or even our faith? If we have to read the Genesis story in the same way that we read…say the resurrection accounts… then I think we have some irreconcilable problems.

But thankfully there’s another way.

This is an Old, Old Story

The story of the flood is ancient. In fact, it’s actually older than the Bible itself. Regardless of when you think the flood account of Genesis 6-9 was written down, the story predates it by hundreds, and possibly even a thousand, years. Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian, and other ancient accounts of this flood story exist and have been provided to us by archaeologists and historians across the ages.

Pete Enns and Jared Byas in their book Genesis for Normal People wrote, “Israel’s ancient neighbors also had flood stories very similar to the biblical one, and (2) Israel’s flood story was written after these other stories (as we saw with the creation story in Genesis 1). These older versions come from ancient Sumeria, Assyria, and Babylon.”1

But why does this matter?

Well, while so many of us ask questions about what happened in history or how it happened, understanding that these other stories existed alongside and even predated the flood story help us shift the question to why would there be a need for yet another flood story.

Typically, when we are talking about Genesis, we get distracted with questions about light being created on day one while the sun was made on day four or questions about how Noah dealt with all of that poop or why God would preserve mosquitos.

But when we shift the question, then a whole new range of answers and meaning comes to life. Like, why did people find this particular version of the story compelling enough to preserve it in writing and pass it down for thousands of years? Why did they write this story when other versions already existed? What were the biblical writers, and the Holy Spirit, trying to accomplish in creating and preserving this story in Scripture?

Same Setup, Different Punchline

So one way to think about what the Bible is doing with stories like the flood story or the creation account is to think about common joke setups we all know.

A guy walks into a bar…

Why did the chicken cross the road?

What’s black, white, and re(a)d all over?

When you start one of these jokes, people will typically groan, but if you change the punchline, you can typically get a laugh or least another groan and maybe even an eye roll if you’re lucky.

What’s black, white, and red all over? A newspaper? No, a zebra with a sunburn.

A guy walks into a bar… ouch.

Two guys walk into a bar… it was a knock-knock joke.

The Bible does this with old stories all the time.

In the beginning… God fought chaos, ripped it in half, and made half of it the heavens and half of it the sea? No. In the beginning God spoke the world into existence with the gentleness of a mother dove who cares for her young.

The same thing is going on with the flood story.

At some point in our collective memory as humans, there was a big flood. And this isn’t too farfetched. If you consider that most people lived around rivers like the Nile, Euphrates, or Tigris then of course there would be stories about floods. Most years, the rains would bring floods that would be beneficial to the civilization. The flood waters leave behind nutrients for the soil, and the worms and vegetation that are swept away make good food for the fish.

But then there’s those years where it rains way more than usual.

During those years, the rains come down and the floods come up and the foolish man’s house goes splat. Couple those kinds of events with Ice Age 2: The Meltdown and you have the makings of a good story to tell around the campfire.

But in those days, the questions about why these kinds of floods happened were not like the questions we ask. We may talk about the weather cycle, patterns of flooding, ice caps melting, high tide and low tide, and any other number of scientific explanations behind catastrophic flood events. In our recent memory, Katrina and the Tsunami of 2004 are testimonies to the destructive power of flood waters, but we still gravitate towards natural explanations involving earthquakes, broken levees, and early warning systems.

But in the days before James Spann and the Doppler radar, the best guess for the cause of these kinds of floods is that the gods must be angry.

And that’s how these ancient stories function. Maybe the gods just randomly decided to flood the world with no explanation given. Perhaps they were worried about overpopulation. And in one story they were simply aggravated that the humans were so noisy.

Anyone who is familiar with a cat’s tendency to get the zoomies at 3am knows what I mean.

And in the stories, the gods originally agree to kill off all of the humans. It’s only due to a leak (ha) that humans learn of the flood and barely escape it.

But in the Bible’s version of this story, the gods aren’t being petty and they don’t make rash decisions; instead, the God who frees slaves is concerned because violence and wickedness is spreading in ever-increasing proportions.

Scripture says,

The LORD saw that the wickedness of humans was great in the earth and that every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only evil continually. Genesis 6:5 (Remember this verse!! Write it down or something. Seriously.)

Now the earth was corrupt in God’s sight, and the earth was filled with violence. Genesis 6:11

So the biblical authors reasoned that the flood must have come because of a justice issue, and God’s preservation of Noah wasn’t because he was double-crossing the other gods but because Noah found favor in God’s sight because he was righteous even though everyone around him had abandoned the image of God.

But Noah found favor in the sight of the LORD. These are the descendants of Noah. Noah was a righteous man, blameless in his generation; Noah walked with God. Genesis 6:8–9

And then, after the flood comes and Noah and his family are saved, the punchline surprises us all: God says this will never happen again. He hangs his bow up.

This promise is actually made twice, once with a rainbow and once without. It’s interesting to me that this first quote is unequivocal whereas the second quote presents a possible exception that is used by Peter later in the Bible:

And when the LORD smelled the pleasing odor, the LORD said in his heart, “I will never again curse the ground because of humans, for the inclination of the human heart is evil from youth; nor will I ever again destroy every living creature as I have done. Genesis 8:21

I establish my covenant with you, that never again shall all flesh be cut off by the waters of a flood, and never again shall there be a flood to destroy the earth. Genesis 9:11

So the story ends (well, almost) with God saying that this will never happen again. The first time he says it, there are no exceptions given. But the second time he says it, he specifies that the earth wouldn’t be destroyed with water, so some people, including one way of reading Peter, say, “Well he won’t destroy it with water, but he will destroy it with fire!”

I don’t really see it that way, but that’s a discussion for another day. Instead, let’s make a quick connection that I think is very cool.

Remember how I told you to keep that passage from Genesis 6 in mind? Well, check this out.

Even Though…

Compare these two passages:

The LORD saw that the wickedness of humans was great in the earth and that every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only evil continually. Genesis 6:5

And when the LORD smelled the pleasing odor, the LORD said in his heart, “I will never again curse the ground because of humans, for the inclination of the human heart is evil from youth; nor will I ever again destroy every living creature as I have done. Genesis 8:21

The very reason for the flood in Genesis 6 is also the reason God cites for committing to never destroying the earth again.

In other words, God commits to stopping the cycle of violence.

Or another way to say it, the flood didn’t stop humans from being bad.

The whole point of the flood story, then, is to say that God doesn’t work that way, that floods aren’t effective discipline tools, and that God can bear with us despite the evil inclinations of our heart.

And they all lived happily ever after… well… not really.

Noah: The Righteous, the Blameless, and the Drunkard

Another song I sang growing up said, “Don’t drink booze. Don’t drink booze. Spend your money on a pair of shoes.”

If you were raised in the non-institutional Church of Christ, the lyrics were, “Don’t drink alcohol. Don’t drink alcohol. It’d be like spending God’s money on a fellowship hall.”

Alright, so apparently Noah didn’t sing either version of this song because the author of Genesis wrote,

Noah, a man of the soil, was the first to plant a vineyard. He drank some of the wine and became drunk, and he lay uncovered in his tent. And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father and told his two brothers outside. Then Shem and Japheth took a garment, laid it on both their shoulders, and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father; their faces were turned away, and they did not see their father’s nakedness. Genesis 9:20–23

Noah became drunk. And while some say that Noah wasn’t aware of the effects of the wine because he was the first to make it, I find it hard to excuse Noah for what he did. In Genesis 3, nakedness brought a sense of shame upon Adam and Eve. And Habakuk 2:15 along with Lamentations 4:21 also comment on the sense of shame related to nakedness coupled with inebriation. But apparently Ham isn’t too concerned with hiding his father’s shame, and some commentators suggest there may even be more going on here.

But I think we are getting too much into the wrong kinds of questions.

Let’s think again why this story might be included. Is it really a necessary part of the story?

Well, in some of the other ancient flood stories, the protagonist receives immortality.

Noah, though, is a guy like you and me who might be considered righteous and blameless in one instance and… well… you know how it goes. Noah isn’t some special, almost demigod who survives the flood and has immortality. He gets drunk, passes out naked, and then wakes up from his wine and curses his grandson for his dad’s actions, which, to be honest, he doesn't really seem like he is in a place where can hand out curses, but maybe that’s just me.

Noah said, “Cursed be Canaan; lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers” (Genesis 9:25).

Ah, but now do you see why this story may have been included? It serves as a way to explain why the Canaanites were destined to be conquered, killed, and even enslaved by Israel.

As Enns and Byas wrote,

The flood story is Israel’s vehicle for talking about how their God is different from the gods of the other nations. It is also a vehicle for the later Israelite writer to explain why the hated Canaanites deserved everything they got, including being violently driven from their homeland so it could be given to the Israelites: they have been an accursed race since the beginning—because Ham saw Noah’s nakedness.2

One Last Bit About Jesus

So if you’re like me, then a lot of this information about the historical and cultural background behind the flood story is super helpful. Knowing that it is basically commentary on the other flood stories that serves to answer the question “What is God like"?” is a huge step forward towards a healthier way to talk about the flood and other ancient stories.

In fact, for them, it was a huge step forward. One might even call this story, in comparison to the other stories floating around (ha) during this time, progressive or revolutionary.

But if you’re like me, then there’s still a voice in the back of your mind going, “Okay, but what about the people who died in the flood? What happened to them?”

Well, I can’t answer that question with 100% certainty, but I can offer one more passage to you that offers some thoughts on the flood story:

For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, in order to bring you to God. He was put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit, in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison, who in former times did not obey, when God waited patiently in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight lives, were saved through water. 1 Peter 3:18–20

For this is the reason the gospel was proclaimed even to the dead, so that, though they had been judged in the flesh as everyone is judged, they might live in the spirit as God does. 1 Peter 4:6

Now there are several ways to take this. One has to do with Jesus preaching through the Holy Spirit to the people of Noah’s day through Noah because Noah was a herald of righteousness (2 Peter 2:5). But I find this personally the most dubious of the three options typically presented.

The other popular option, and probably the most popular among scholars today, is that Jesus proclaimed victory over the fallen angels (see 1 Peter 3:22). This is a better option than the one mentioned above because there is some evidence that the actions of fallen angels led to the flood (Genesis 6:1-4; and possibly 2 Peter 2:4-5). But to be honest, I just don’t buy the Nephilim theory or the Divine council theory in Genesis 1, 6, or other passages. I know I’m in the minority here among a lot of my readers and listeners, but I just don’t find the arguments compelling personally.

Instead, I interpret the “spirits” in prison as the ones who refused to hear Noah’s call to repentance, died in the flood, and then found themselves in Hades. God waited patiently for them to repent, which is the imagery Peter later uses in regards to the second coming (2 Peter 3:6-9). Jesus, not willing that any should perish and desiring all to be saved, offered salvation to them as well. He proclaimed the good news to the dead so that they may live in the spirit according to the will of God (1 Peter 4:6).

Many of the church fathers held similar interpretations of this confusing passage. While I know that it is an appeal to an authority, which is a logical fallacy, their testimonies show that I am not alone in viewing the passage this way.

Cyril of Alexandria:

Going in his soul, he preached to those who were in hell, appearing to them as one soul to other souls. When the gatekeepers of hell saw him, they fled; the bronze gates were broken open, and the iron chains were undone. And the only-begotten Son shouted with authority to the suffering souls, according to the word of the new covenant, saying to those in chains: “Come out!” and to those in darkness: “Be enlightened.” In other words, he preached to those who were in hell also, so that he might save all those who would believe in him.3

Prudentius:

That the dead might know salvation,

who in limbo long had dwelt,

Into hell with love he entered;

to him yield the broken gates

As the bolts and massive hinges

fall asunder at his word.

Now the door of ready entrance,

but forbidding all return

Outward swings as bars are loosened

and sends forth the prisoned souls

By reversal of the mandate,

treading its threshold once more.

Others include Origen, Clement of Alexandria, Servus of Antioch, and Ammonius, but they all vary on the details as one would expect.

The point though is that God is righteous and God is love. If we can trust in those two points, which are really the same point, then I think we can trust that all shall be well and all manner of things shall be well. How it all worked out or how it all will work out may be unknown to us, but we can trust that mercy triumphs over judgment and that the good news is in fact good news… even for people like you and me who struggle with these sorts of things.

Enns, Peter; Byas, Jared. Genesis for Normal People: A Guide to the Most Controversial, Misunderstood, and Abused Book of the Bible (Second Edition w/ Study Guide) (The Bible for Normal People) (p. 52). The Bible for Normal People. Kindle Edition.

Enns, Peter; Byas, Jared. Genesis for Normal People: A Guide to the Most Controversial, Misunderstood, and Abused Book of the Bible (Second Edition w/ Study Guide) (The Bible for Normal People) (p. 60). The Bible for Normal People. Kindle Edition.

Bray, Gerald, ed. James, 1-2 Peter, 1-3 John, Jude. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000. Print. Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture.